Around mid-year, Lab52 published a report on ransomware that included both geopolitical and cyber intelligence content. The report includes the analysis of different sources of information and showcasing some of our cyberintelligence findings in this regard.

However, the activity of this type of malware prompts Lab52 to closely track the various recorded cases. Therefore, taking advantage of the approaching end of the year 2023, we believe it’s a good time to share some reflections contributed by our team, furthermore, especially considering the latest news about BlackCat and Lockbit.

This is a very realistic Ransomware’s Christmas Carol from Lab52, considering three main pillars: cyberintelligence, geopolitical and malware analysis key aspects identified during 2023.

This post focuses on the following aspects:

- Key findings from the July report

- Top-10 ransomware per quarter in 2023

- BlackCat and Lockbit

- Ransomware and financial sector

- Ransomware evolution – analytical point of view

Key findings from the July report

The report is extensive and is written in Spanish, so here we provide some of the general results that can be observed. It has been born from the cooperation among the cyberintelligence, geopolitical, and malware teams within S2 Grupo, which together form Lab52, such as this post.

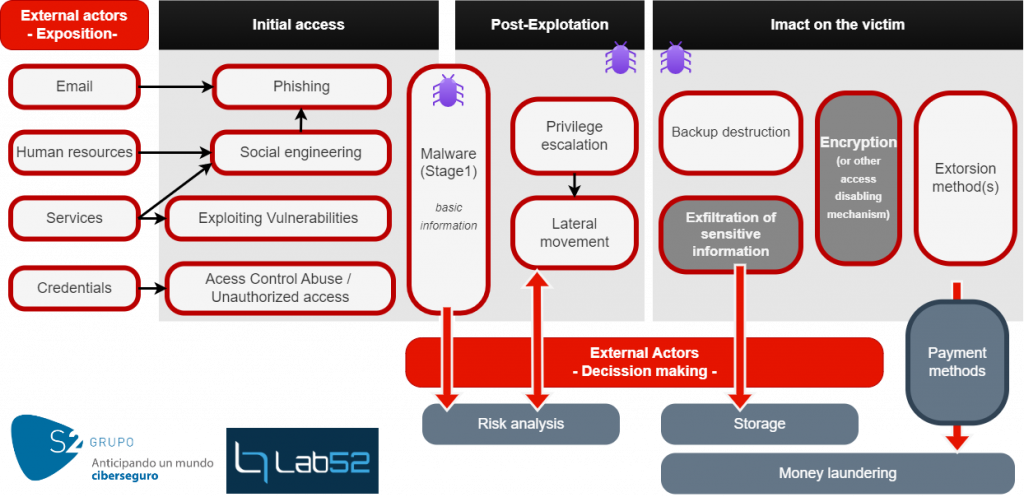

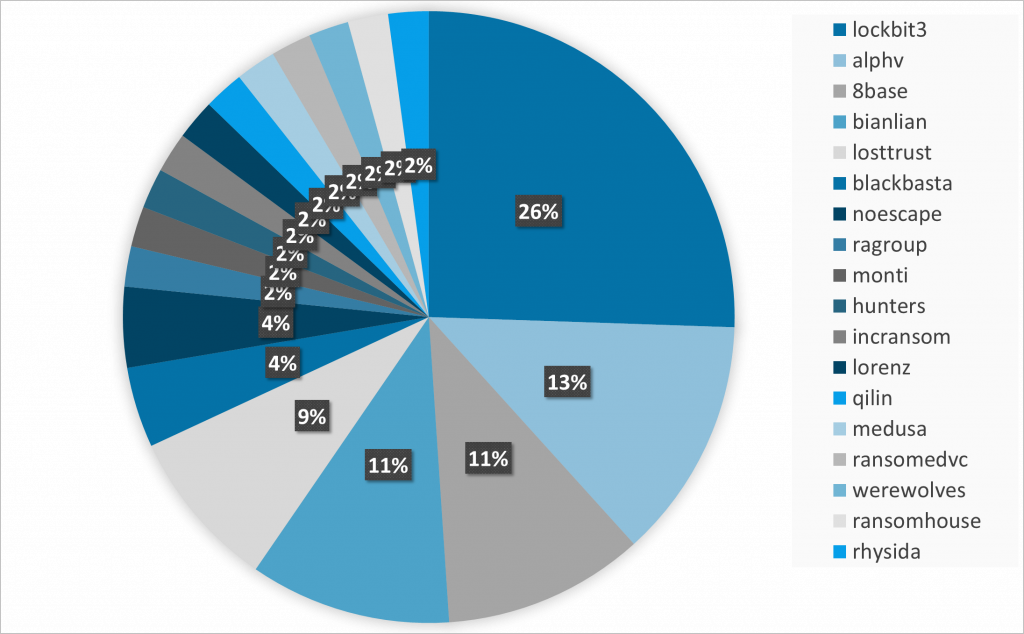

The report addresses both observed operational models and the geopolitical impact on the evolution of ransomware, as well as the technical focus of the tools used by cybercriminals. The report highlights the following active groups: LockBit, BlackCat (ALPHV), BianLian, Cl0p, Royal, and Black Basta. As expected, special mention is made of the avenues of protection against ransomware.

Perhaps, among the most notable aspects is the rise of new ransomware groups taking advantage of the decline of renowned groups like Conti to emerge. The report also addresses the relationship between these new and previous groups, highlighting the established and consolidated chain of profit among the groups.

The change in operations in recent years is evident, and one of the turning points may lie in the fact that major ransomware groups now have versions for both Windows and Linux, with the added capability of targeting virtualization servers. Therefore, the current scope is greater. Another significant variation is the increasing trend to shift from the encryption + exfiltration + extortion model to the exfiltration + extortion model, bypassing the encryption phase.

Top-10 ransomware per quarter in 2023

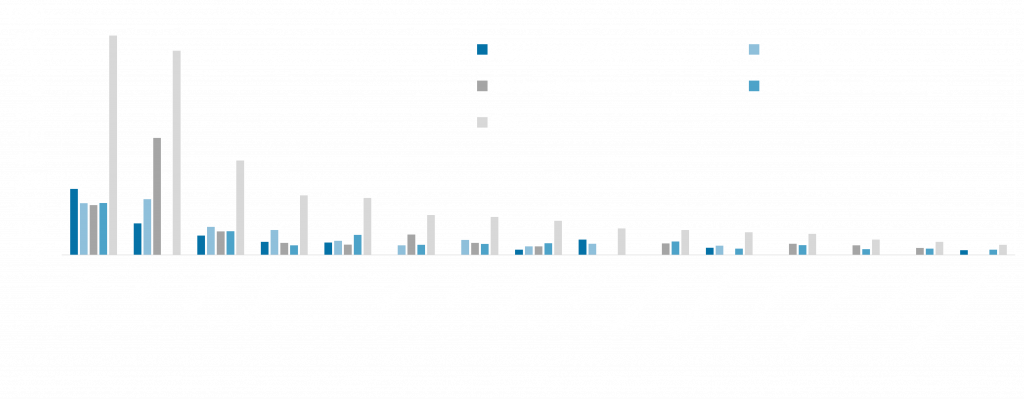

The following graph illustrates the evolution of ransomware in terms of the number of victims reported throughout the year 2023. The order in the graph is given by the total number of victims per group. The data collected corresponds to the period January 1st to December 21st, 2023. It’s worth noting that, even without registering victims during the last quarter of the year, Cl0p ranks second, following Lockbit.

The third ransomware in this Top-10 rank is BlackCat (aka ALPHV). This is even more interesting, given the recent announcement by the FBI regarding the group BlackCat’s intervention, and the offert , and the subsequent recruitment offer by Lockbit aimed at members of BlackCat. This has made us wonder, what would happen from a technical standpoint if developers from both teams combined efforts?

BlackCat and Lockbit

In the June report, the relevance and importance of Lockbit and BlackCat were highlighted. Some of their characteristics detailed in the report are displayed below. Indeed, in that report, they held the top two positions, as Cl0p began its ascent in the number of victims later in the year. From a hihg level point of view, both ransomware groups have similar tactics, and, something that is particularly noteworthy is that both maintain their own exfiltration tools. This means that both groups have developers with capacity to understand how this can be done and how these tools can be improved to avoid detection.

| Phase | Lockbit | BlackCat |

| Initial access | Phishing, RDP explotaition, credential abuse, vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange servers. Support for: windows, linux and VMWare ESXi servers | Phishing, RDP explotaition, credential abuse, vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange servers. Support for: windows, linux and VMWare ESXi servers |

| Execution | Command execution, privilege escalation. UAC Bypass. escalation, enumeration, process and service termination, persistence, log and resource deletion. Lateral movement through hardcoded credentials in the code or through the compromise of privileged accounts. | Configurable according to the affiliate, allowing for self-propagation. Command execution, privilege escalation. UAC Bypass. Enumeration of domains and devices. Modification of the boot loader, deletion of shadow copies, cleaning Windows events. Lateral movement using SMB and other techniques. In Windows systems, it uses legitimate versions of PsExec embedded in the code. |

| Exfiltration | Custom tool Stealbit for data exfiltration and uploading to cloud sharing services. | Custom tool, Exmatter for data exfiltration uploading to cloud sharing services. |

| Encryption | Data encryption on local or remote devices while maintaining system functionality operational. | Improvements introduced in 2022 to support encryption on ARM architectures and for secure mode encryption (with or without network). |

| Additional characteristics | Use of a wide variety of open-source tools. | According to various analysts, several affiliates of Conti have redirected their resources to BlackCat after the former disappeared from the scene. |

Some additional characteristics about BlackCat are:

- Remote symbolic links:

- It uses the commands “fsutil behavior set SymlinkEvaluation R2L:1” and “fsutil behavior set SymlinkEvaluation R2R:1” to allow the creation of remote-to-local and remote-to-remote symbolic links. This could be employed by threat actors to gain remote access to a directory on the infected system. For instance, through the command “mklink /D C:\Share \IP\C$”, it creates a symbolic link under the “Share” folder to the default shared folder of the established server.

- Execution access token:

- BlackCat utilizes an access token (key) for decrypting the configuration. This key is necessary, as the ransomware won’t execute without successfully decrypting the configuration. Lockbit implemented a similar behavior in its 3.0 version. The difference lies in Lockbit decrypting part of the code that will be executed, rather than the configuration, potentially leading to increased entropy.

- Signed kernel drivers:

- BlackCat has been observed using signed drivers. These drivers lack a “DriverUnload” function, preventing the driver from being stopped via the “sc stop” command. It supports a total of 10 supported commands. Before any command can be invoked, the driver must be activated by passing an array of bytes, which is compared with a hardcoded array in the binary. If this function isn’t called first, the driver won’t allow any operation and will return the error STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED.

In addition, LockBit presents the following characeristics:

- Changes behavior when running in safe mode:

- If Lockbit runs while the computer is in safe mode, it won’t encrypt; instead, it will create a registry key to execute during the next normal system boot.

- Detects system language to avoid execution:

- Lockbit retrieves the language of the computer and cross-references it with the list contained in the configuration. This list includes languages like Romanian (Moldova), Arabic (Syria), and Tatar (Russia), although this list may expand. If any of these languages are detected on the system, Lockbit won’t execute.

- Disabling EDR processes and services:

- They utilize tools like Backstab, Defender Control, GMER, PCHunter, PowerTool, Process Hacker, or TDSSKiller to disable EDR processes and services.

Finally, both require an access token (key) to execute. However, Lockbit uses it to decrypt encrypted sections, whereas BlackCat employs it solely to decrypt its configuration.

Ransomware and financial sector

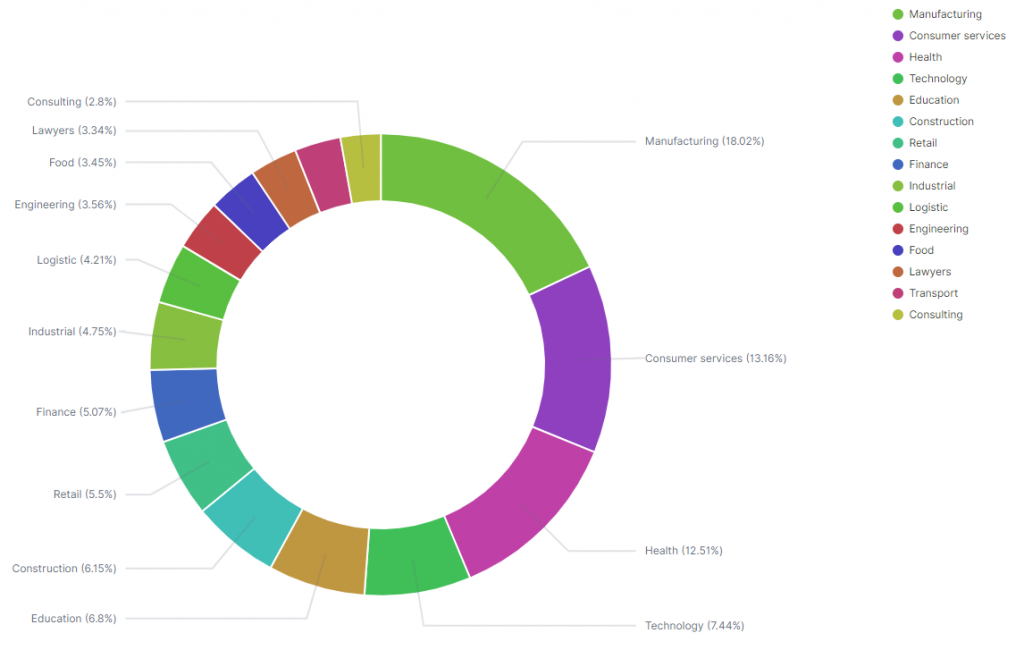

The financial sector, like others, is also affected by ransomware infections. The following graph shows the groups targeting this sector. Particularly, these are data from the last quarter of the year. It can be seen that the strongest ransomware groups also severely attack this sector, which is one of the reasons why this issue is increasingly addressed here.

However, in the overall count of affected sectors, considering the 15 most affected sectors by ransomware, the registered victims from this sector represent around 5%.

The impact on the financial sector can be motivated by the expectations of payment and because is one of the sectors saving more personal data, where to maintain the customer’s trust is critical.

However, it is important to remember that there have always been incidents. This increasing in the incidents is only part of the natural evolution of cybercrime.

Ransomware evolution – analytical point of view

From the perspective of ransomware analysis, its evolution is part of the inherent nature of software development, although from a security improvement standpoint; well-organized groups protect the software they develop as the valuable asset it is.

Previously, examples like Blackbit and Lockbit were shown; these groups use their own tools, constantly enhancing and maintaining them. Leaks of tools maintained by ransomware groups enable analysts to develop solutions in the form of rules or vaccines to prevent their execution. That said, one might anticipate new leaks following the BlackCat intervention, allowing the analyst community to bolster defenses. However, it can also lead to an improvement in malware when considering the exploitation or reuse of code, and the learning of other smaller ransomware groups that see these leaks as an opportunity to enhance their techniques at a lower cost.

For example, as seen in the case of Lockbit with the release of its builder, other actors take advantage to generate their own malicious code, which could mark the beginning of new campaigns by actors who, despite not being BlackCat, exploit their arsenal.

In addition, there are typical characteristics shared by different ransomware families are, for example:

- Log cleaning (wevtutil).

- Deletion of shadow copies (vssadmin or wmic).

- Obtaining credentials as an initial access method.

- Discovery of shared folders in the network.

- Changing the desktop background.

- Utilization of configuration files.

- Propagation via Group Policy.

While such characteristics may already be considered commonplace in the analysis of any ransomware, one must not forget the following points that could be deemed critical in the evolution of ransomware:

- The code modularization, particularly safeguarding the group’s most valuable assets (software), leads to a secure ransomware deployment phase where the system has been compromised and is at the mercy of the operators. As part of this modularization, several ransomware are deployed using a token or key for their execution provided by the C2 (Command and Control) server. Additionally, this modularization further justifies system resource monitoring to log all actions and allow memory dumps, ensuring maximum available information for future incident analysis and the potential (unlikely) data recovery.

- Software protection through tools like Themida or VMProtect complicates its analysis. Advanced malware samples are heavily shielded precisely because they represent a crucial asset for the organization.

- Multiple extortion allows cybercriminals, in many cases, not to encrypt all content, being selective. Even if the victim keeps backups of the data, the mere threat of its publication can be reason enough to pay the ransom. Therefore, this also allows greater flexibility in the new development of ransomware, where encryption speed remains important, but so do the initial exfiltration phases. This justifies much more investment in the development of such utilities.

- Support for multiple operating systems,including support for virtual machine servers. In fact, the different versions have their own peculiarities. For instance, the Qilin (Agenda) ransomware uses a random password in the Windows version, while in the Linux version, it does not.

These are some examples that allow ransomware to proliferate as a significant asset for cybercriminals. However, they will continue evolving as society does.

Conclusions

Like the July report anticipated, the downfall of certain ransomware groups benefits others. Over the past few years, there has been a noticeable professionalization in this sector. Malware is being treated as a valuable asset, and in a ransomware attack, understanding the compromise chain is crucial for preparing better defenses. Unfortunately, this is not always possible, precisely due to the modularity of the code and the security precautions taken by more advanced cyber attackers.

Regarding malware development, it’s also worth noting the impact that a data leak has on the broader community: cybersecurity analysts strengthen their defenses and leverage this knowledge, but so do other actors with lower profiles and fewer resources. They learn from the leaked code, make their own adaptations, and employ it in new waves of attacks. That’s why it’s essential to stay informed and cautiously approach news related to this sector.

Also, during this 2023, the financial sector has been one of the most affected by this type of malware; as mentioned, it’s due to the inevitable improvement in the capabilities of ransomware groups. No sector can consider itself exempt. While it’s true that preventive measures are known and adopted by many companies nowadays (for example, backups), ransomware groups have also adapted to this situation, reinforcing their data exfiltration capabilities to pressure victims with multiple extortion attempts.

Finally, we don’t know what 2024 holds for this particular threat, but we do know that the possibilities opened by AI from a developmental standpoint can contribute to the creation of new malware assets. How we face this new challenge will largely depend on our ability to adapt sooner and better than our adversaries.

Leave a Reply